Profiling a simulation’s performance¶

The following outlines how to tackle a simulation that is running too slow.

Since 34.4.0 it is possible to generate a time performance flame graph in a web page to view the time taken by every calculation in a simulation.

The following examples utilise the OpenFisca-France package but the profiling is available to any package.

Identify a slow simulation¶

The easier way to spot a slow simulation is to profile a test suite, as follows:

PYTEST_ADDOPTS="$PYTEST_ADDOPTS --durations=10" openfisca test --country-package openfisca_france tests

...

This returns the 10 slowest tests:

9.69s call tests/test_basics.py::test_basics[scenario_arguments12]

9.02s call tests/reforms/test_plf2016_ayrault_muet.py::test_plf2016_ayrault_muet

8.91s call tests/test_basics.py::test_basics[scenario_arguments11]

8.78s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

8.44s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

8.37s call tests/formulas/revenu_disponible.yaml::

8.36s call tests/formulas/revenu_disponible.yaml::

8.27s call tests/formulas/revenu_disponible.yaml::

8.23s call tests/formulas/revenu_disponible.yaml::

8.17s call tests/test_tax_rates.py::test_marginal_tax_rate

Profile tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml from the above results:

PYTEST_ADDOPTS="$PYTEST_ADDOPTS --durations=3" openfisca test --country-package openfisca_france tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml

...

9.03s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

7.75s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

3.02s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

This indicates the first test in tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml is the slowest, compared to the others.

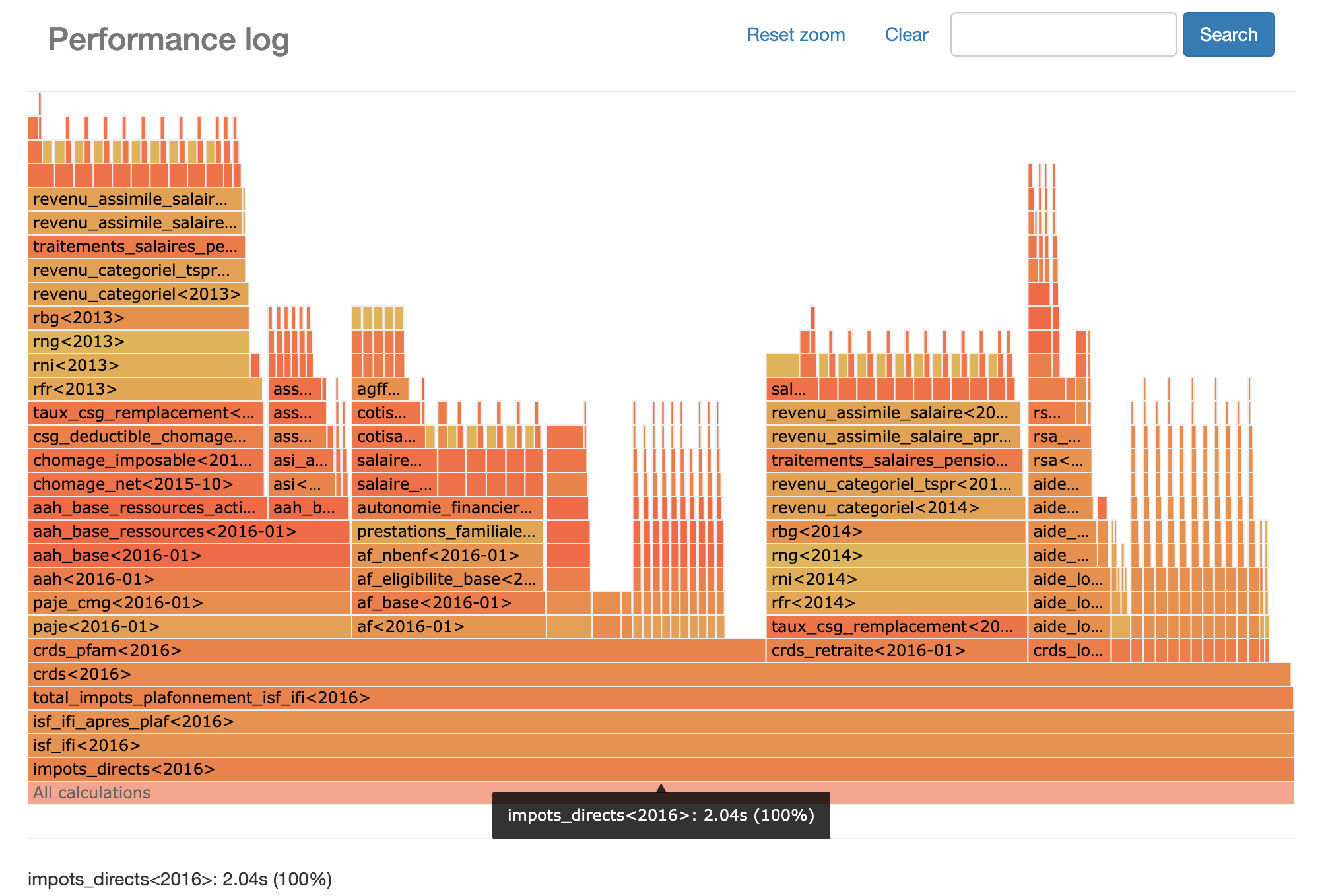

Generate the flame graph¶

To generate the flame graph, pass the --performance option to openfisca test.

It is also possible to supply the --name_filter option to profile specific tests only.

openfisca test --performance --name_filter ir_prets_participatifs_2016 --country-package openfisca_france tests/formulas

git status | grep html

...

performance_graph.html

Open the flame graph¶

Now, you can open the file with your favourite browser.

For example, in OS X:

open performance_graph.html

You’ll be greeted by a very nice looking flame graph like this one:

Looking at the graph, we now know that the impots_directs formula takes quite a lot of time.

The question is, why?

Find the bottleneck¶

In order to identify why the simulation is slow, we need to find the bottleneck. We’ll use a line profiler to figure it out.

We’ll start by installing line_profiler:

pip install line_profiler

Then we’ll use it to profile our formula by adding the @profile decorator:

class impots_directs(Variable):

value_type = float

entity = Menage

label = "Impôts directs"

reference = "http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imp%C3%B4t_direct"

definition_period = YEAR

@profile

def formula(menage, period, parameters):

Finally, we run our test with the line_profiler enabled:

kernprof -v -l openfisca test --name_filter ir_prets_participatifs_2016 --country-package openfisca_france tests/formulas

We now know where our most time consuming line lies:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

====================================================================

635 1 3488880.0 3488880.0 100.0 isf_ifi_i = menage.members.foyer_fiscal('isf_ifi', period)

Another formula… so we’ll have to follow the breadcrumbs.

Follow to the core¶

We’ll continue our profiling in core, following TaxBenefitSystem.get_parameters_at_instant.

For that, we need to install OpenFisca Core in editable mode:

pip install -e /path/to/openfisca-core

And as before we add the @profile decorator:

@profile

def get_parameters_at_instant(self, instant):

Let’s see:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==============================================================

337 @profile

338 def get_parameters_at_instant(self, instant):

339 """

340 Get the parameters of the legislation at a given instant

341

342 :param instant: string of the format 'YYYY-MM-DD' or `openfisca_core.periods.Instant` instance.

343 :returns: The parameters of the legislation at a given instant.

344 :rtype: :any:`ParameterNodeAtInstant`

345 """

346 4351 4124.0 0.9 0.2 if isinstance(instant, Period):

347 4254 5094.0 1.2 0.2 instant = instant.start

348 97 101.0 1.0 0.0 elif isinstance(instant, (str, int)):

349 instant = periods.instant(instant)

350 else:

351 97 54.0 0.6 0.0 assert isinstance(instant, Instant), "Expected an Instant (e.g. Instant((2017, 1, 1)) ). Got: {}.".format(instant)

352

353 4351 3732.0 0.9 0.2 parameters_at_instant = self._parameters_at_instant_cache.get(instant)

354 4351 2108.0 0.5 0.1 if parameters_at_instant is None and self.parameters is not None:

355 50 2043730.0 40874.6 99.2 parameters_at_instant = self.parameters.get_at_instant(str(instant))

356 50 150.0 3.0 0.0 self._parameters_at_instant_cache[instant] = parameters_at_instant

357 4351 1672.0 0.4 0.1 return parameters_at_instant

Let’s take a closer look at parameters.get_at_instant:

class AtInstantLike(abc.ABC):

# ...

@profile

def get_at_instant(self, instant):

instant = str(periods.instant(instant))

return self._get_at_instant(instant)

And the results of running the profiler:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==============================================================

14 @profile

15 def get_at_instant(self, instant):

16 54550 681341.0 12.5 61.4 instant = str(periods.instant(instant))

17 54550 429057.0 7.9 38.6 return self._get_at_instant(instant)

This is the whole snippet for the expensive periods.instant function:

def instant(instant):

# ...

if isinstance(instant, str):

# ...

instant = periods.Instant(

int(fragment)

for fragment in instant.split('-', 2)[:3]

)

We’ll refactor it as follows:

fragments = instant.split('-', 2)[:3]

fragments = [int(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

instant = periods.Instant(fragment for fragment in fragments)

So as to see where the bottleneck is:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==================================================================

40 44100 223427.0 5.1 31.4 fragments = [int(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

Perfect!

Isolate the bottleneck¶

Now we’re going to isolate it:

fragments = instant.split('-', 2)[:3]

fragments = [parse_fragment(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

instant = periods.Instant(fragments)

# ...

@profile

def parse_fragment(fragment: str) -> int:

return int(fragment)

And profile it again:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==================================================================

40 44100 442069.0 10.0 52.2 fragments = [parse_fragment(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

210 132300 72826.0 0.6 100.0 return int(fragment)

Elevate the bottleneck¶

Now we need to choose a strategy to reduce the bottleneck’s impact on performance.

We can either:

reduce the impact per hit

reduce the number of hits

Taking a look at the last line we profiled, we can see that:

time per hit is very low —implementing a casting algorithm more efficient than the builtin

intseems unlikelythe range of reasonable values for the

fragmentargument is very low: 31 days, 12 months, 2021 → 2064there are 132300 hits, and that’s just for a single simulation (!)

So let’s try to reduce the number of hits!

Once again, we could for example:

reduce recursion

create a lookup table

In this case, creating a lookup table seems more cost-efficient:

the function application has no side effects

the range of reasonable values for

fragmentis very lowreturn values are identical for identical values of

fragment

We’ll use functools.lru_cache for our lookup table:

import functools

# ...

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize = 100)

def parse_fragment(fragment: str) -> int:

return int(fragment)

Let’s see how it does:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==================================================================

355 50 1809954.0 36199.1 99.0 parameters_at_instant = self.parameters.get_at_instant(str(instant))

16 44100 421208.0 9.6 49.0 instant = str(periods.instant(instant))

41 44100 97584.0 2.2 20.6 fragments = [parse_fragment(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

212 17 40.0 2.4 100.0 return int(fragment)

Wow! The number of hits to parse_fragment decreased by 99%, improving the generator performance by 353%!

That’s it!

Caching further¶

Once we know it works, can’t we go further?

With a couple of extra caches and code refactoring, we could end up with something like this:

from __future__ import annotations

# ...

import functools

# ...

from typing import Optional

# ...

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize = 1000)

def instant(instant) -> Optional[periods.Instant]:

if instant is None:

return None

if isinstance(instant, str):

if not config.INSTANT_PATTERN.match(instant):

raise_error(instant)

fragments = instant.split('-', 2)[:3]

integers = [parse_fragment(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

instant = periods.Instant(integers)

elif isinstance(instant, datetime.date):

instant = periods.Instant((instant.year, instant.month, instant.day))

elif isinstance(instant, int):

instant = (instant,)

elif isinstance(instant, (list, tuple)):

assert 1 <= len(instant) <= 3

instant = tuple(instant)

elif isinstance(instant, periods.Period):

instant = instant.start

elif isinstance(instant, periods.Instant):

return instant

else:

return instant

return globals()[f"instant_{len(instant)}"](instant)

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize = 1000)

def parse_fragment(fragment: str) -> int:

return int(fragment)

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize = 1000)

def instant_1(instant: periods.Instant) -> periods.Instant:

return periods.Instant((instant[0], 1, 1))

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize = 1000)

def instant_2(instant: periods.Instant) -> periods.Instant:

return periods.Instant((instant[0], instant[1], 1))

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize = 1000)

def instant_3(instant: periods.Instant) -> periods.Instant:

return periods.Instant(instant)

Please note that we’re importing annotations from __future__ so as to postpone the evaluation of type annotations (PEP484 and PEP563), in order to avoid cyclic imports.

Let’s profile again:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

===================================================================

355 50 1787843.0 35756.9 98.8 parameters_at_instant = self.parameters.get_at_instant(str(instant))

16 44100 92290.0 2.1 14.1 instant = str(periods.instant(instant))

48 50 349.0 7.0 22.2 integers = [parse_fragment(fragment) for fragment in fragments]

213 17 76.0 4.5 100.0 return int(fragment)

And overall?

PYTEST_ADDOPTS="$PYTEST_ADDOPTS --durations=3" openfisca test --country-package openfisca_france tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml

...

7.33s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

7.16s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

2.46s call tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml::

Looks promising!

Beware of context¶

So we tried reducing the number of hits, what about reducing the impact per hit?

Looking back to get_at_instant, let’s follow the next function call:

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

===================================================================

16 44100 76860.0 1.7 15.4 instant = str(periods.instant(instant))

17 44100 421350.0 9.6 84.6 return self._get_at_instant(instant)

Let’s look at that code closer:

def _get_at_instant(self, instant):

for value_at_instant in self.values_list:

if value_at_instant.instant_str <= instant:

return value_at_instant.value

return None

A linear search! I know what you’re thinking, what if we do a binary search instead?

Let’s try that out (naive implementation):

+import sortedcontainers

# ...

class Parameter(AtInstantLike):

# ...

def __init__(self, name, data, file_path = None):

#...

values_list = []

+ values_dict = sortedcontainers.sorteddict.SortedDict()

# ...

values_list.append(value_at_instant)

+ values_dict.update({instant_str: value_at_instant})

self.values_list: typing.List[ParameterAtInstant] = values_list

+ self.values_dict = values_dict

# ...

def _get_at_instant(self, instant):

- for value_at_instant in self.values_list:

- if value_at_instant.instant_str <= instant:

- return value_at_instant.value

- return None

+ index = self.values_dict.bisect_right(instant)

+

+ if index > len(self.values_list):

+ return None

+

+ return self.values_list[::-1][index - 1].value

And performance wise?

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

===================================================================

16 44100 82468.0 1.9 10.6 instant = str(periods.instant(instant))

17 44100 696812.0 15.8 89.4 return self._get_at_instant(instant)

177 196150 596129.0 3.0 65.8 index = self.values_dict.bisect_right(instant)

It’s actually worse… but why?

One hypothesis is, even if, compared to a linear search with complexity O(n), a binary search should be more efficient in that it has a complexity of O(log(n)), it will actually be more efficient for large numbers of n, which is not usually the case here.

In fact, creating a lookup table for parameters would be theoretically more efficient. That would require refactoring, as the current values_list object is not hashable. Indeed, even using a more appropriate data structure could lead to better performance.

Wrap up¶

Finally, let’s run our base & proposed scenarios several times so as to have something more statistically sound.

IPython’s %timeit comes handy:

pip install ipython

ipython

%timeit -n 10 -r 3 openfisca test --country-package openfisca_france tests/formulas/irpp_prets_participatifs.yaml

# Before

17.2 s ± 261 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 3 runs, 10 loops each)

# After

17.1 s ± 49.2 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 3 runs, 10 loops each)

Statistically irrelevant :/ but hey! Life is about the journey, not the destination :)

But now what? Reduce recursion? But how? Split-Apply-Combine?

To be continued…